From Designation to Leverage: Trump’s New Nigeria Gambit on Religious Freedom

On January 22, 2026, senior officials from Washington and Abuja gathered in Nigeria’s capital for the first meeting of the U.S.–Nigeria Working Group on security and religious freedom. The joint communique was diplomatic but unusually blunt: the Working Group exists “in response to the designation of Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern” by President Donald J. Trump, and its explicit purpose is to “reduce violence against vulnerable groups in Nigeria, particularly Christians.” In a country whose government still insists there is “no religious persecution,” this language marks a sharp turn.

It also reveals something larger about Trump’s foreign policy. In his second term, the president has resurrected the International Religious Freedom Act (IRFA) as both a moral frame and an instrument of pressure, but without embedding it in a coherent strategy. Nigeria’s renewed CPC designation and the new Working Group are a test case: can this mix of public condemnation, threats, and bilateral working-level cooperation produce real protection for Christians and other vulnerable communities, or will it become one more episode where religious freedom is invoked loudly and delivered weakly?

A designation that was “long overdue” and politically charged

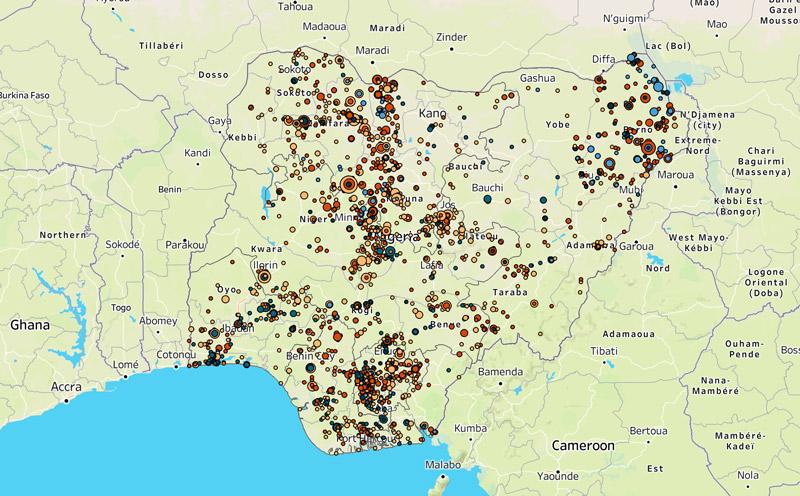

For years, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF) has documented systematic, ongoing, and egregious violations against Christians and other religious communities in Nigeria’s north and Middle Belt. Terrorist groups like Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa, along with other armed actors, have killed tens of thousands and displaced more than 2 million people, targeting churches, pastors, mosques, markets, and entire villages. USCIRF repeatedly recommended that Nigeria be designated a Country of Particular Concern under IRFA, but for years those recommendations went nowhere.

Under Trump’s first term, Nigeria briefly landed on the CPC list in 2020, only to be removed by Secretary of State Antony Blinken in 2021 without detailed public justification—a move that infuriated religious freedom advocates. By 2025, after a new wave of attacks, U.S. lawmakers, human rights organizations, and Christian advocacy networks were again calling the designation “necessary and long overdue.” Analyses with titles like “Nigeria’s Christians Under Siege: Why the CPC Designation Was Long Overdue” became common in U.S. religious freedom circles.

Trump seized that moment. In late 2025 he announced that Nigeria would be redesignated a CPC, explicitly citing attacks on Christians and accusing Abuja of tolerating or abetting violence. Members of Congress followed with bills like the Nigeria Religious Freedom Accountability Act, calling for targeted sanctions on Nigerian officials who facilitate religious violence or enforce repressive blasphemy laws. Advocacy groups welcomed the move as long‑awaited recognition that “the Nigerian government has not done everything they could” to protect its citizens.

Abuja’s reaction was defensive and furious. Nigerian officials rejected the designation as “based on faulty data,” insisted that “there is no religious persecution in Nigeria,” and cast Trump’s rhetoric as an oversimplification that weaponizes religion and ignores complex local drivers of violence. The African Union warned against narratives that “conflate all violence with a single religious‑target narrative,” even as it acknowledged grave security failures. For many Nigerians, Trump’s threats of sanctions and even air strikes against “Islamic extremists” sounded less like human rights advocacy and more like a blunt instrument.

It is in this polarized context that the new Working Group has been born.

A high‑level Working Group with an ambitious mandate

The joint statement issued from Abuja is unusually frank about why the Working Group exists and what it is supposed to do. It states clearly that the body was “established in response to the designation of Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern” and that its objectives are to reduce violence against “vulnerable groups in Nigeria, particularly Christians,” and to “create a conducive atmosphere for all Nigerians to freely practice their faith unimpeded by terrorists, separatists, bandits, and criminal militias.”

On the Nigerian side, the delegation was led by National Security Advisor Nuhu Ribadu and included representatives from ten ministries and agencies. On the U.S. side, Under Secretary of State Allison Hooker headed a delegation drawn from eight federal agencies. The agenda spanned security realignments in the North‑Central states, civilian protection, accountability, and enhanced counter‑terrorism cooperation, including technology sharing, anti‑money‑laundering, counter‑terrorist financing, and law enforcement capacity building.

The communique emphasizes shared values: pluralism, the rule of law, sovereignty, and constitutional guarantees of freedom of religion or belief. It repeatedly stresses the need to protect civilians “particularly members of vulnerable Christian communities” and to hold perpetrators accountable for violence, no matter their affiliation. In diplomatic language, this is as close as Abuja has come in recent years to accepting that Christian communities are specifically at risk and that the Nigerian state has not done enough.

At first glance, this looks like a victory for the religious freedom movement: U.S. pressure has not only produced a CPC redesignation but also a structured, bilateral mechanism where Washington can press for concrete improvements. Yet Trump’s broader record on international religious freedom complicates the picture.

Religious freedom as rhetoric and leverage, not strategy

Trump’s first term included significant IRF activity: appointing an ambassador‑at‑large, convening ministerial, and supporting initiatives like the Potomac Declaration. But his 2025 National Security Strategy largely sidelines religious freedom, mentioning it only in passing in the context of “elite‑driven, anti‑democratic restrictions on core liberties” in the West, and saying little about defending persecuted Christians abroad. Analysts note that the document reorients U.S. strategy toward great‑power competition and hemispheric priorities, leaving IRF advocates to ask where, exactly, religious freedom fits in.

At the same time, Trump has deployed IRF language aggressively in specific cases. In Nigeria, he has publicly condemned the killing of Christians, threatened sanctions and even military strikes, and now used the CPC label as a lever to launch a high‑level Working Group. This has thrilled many Christian advocacy groups, particularly those who felt abandoned during the period when Nigeria was removed from the CPC list.

The risk is that religious freedom becomes a selective instrument, deployed loudly in some cases that resonate with domestic constituencies (like Nigerian Christians) while being downplayed or ignored elsewhere—and not tied to a sustained, resourced strategy. As one analysis of the 2025 NSS warns, “the absence of IRF in the 2025 NSS should be a warning sign for IRF advocates,” suggesting that ad hoc actions are no substitute for a coherent policy.

For Nigeria’s communities under threat, what matters is not whether Trump talks about Christian persecution, but whether the U.S.–Nigeria Working Group delivers measurable changes in security, justice, and governance.

What will count as success, for Nigerians, not Washington

To move beyond symbolism, the Working Group should be judged against three sets of outcomes.

First, tangible protection for at‑risk communities. It is not enough to reorganize security forces on paper; protection has to be felt in villages that have seen repeated massacres. That means more than temporary deployments after high‑profile attacks. It requires early‑warning systems, local liaison structures that connect communities to rapid‑response units, and predictable patrols in vulnerable areas of the Middle Belt and North. The Abuja statement notes “realignment of resources to address insecurity, particularly in the North Central states,” but those realignments must be transparent and trackable if they are to reassure the communities that have lost faith in federal promises.

Second, real accountability, moving from impunity to prosecutions. As U.S. lawmakers and USCIRF have highlighted, one of the most damaging patterns in Nigeria is the absence of justice after attacks. Villages are burned, churches destroyed, hundreds killed, and yet arrests are rare and prosecutions rarer still. In my own work on maritime security in the Gulf of Guinea, I have described a similar dynamic: capture without conviction becomes temporary disruption, not deterrence. The same logic holds inland. If perpetrators, whether terrorist groups, ethnic militias, or complicit officials, are not investigated, prosecuted, and sentenced in credible courts, the cycle of violence will continue.

The Working Group’s references to “holding perpetrators of violence accountable” should be operationalized into clear benchmarks: a target number of fully prosecuted landmark cases within a defined timeframe; joint U.S.–Nigerian support for witness protection and forensic capacity; and transparent public reporting on investigations after major incidents. Without this, security cooperation risks focusing on kinetic operations while leaving the culture of impunity intact.

Third, avoiding a sectarian security frame. The CPC designation, public advocacy, and the Working Group’s communique all highlight attacks on Christians, and there is abundant evidence that Christian communities have borne a disproportionate share of recent mass killings in some regions. But as African Union statements and some analysts caution, “conflating all violence with a single religious‑target narrative may hinder effective solutions and destabilize communities.”

Many Muslims, traditionalists, and others have also been victims of Boko Haram, ISWAP, and bandit groups. The long‑term goal should be a civic, non‑sectarian security order in which the state protects all citizens equally, and in which IRF advocacy reinforces equal citizenship rather than framing Nigerian politics as a binary war of Christians versus Muslims. That requires careful messaging from both Washington and Abuja, and genuine inclusion of diverse Nigerian civil society actors, church leaders, Muslim scholars, women’s associations, and human rights organizations, in the Working Group’s ongoing dialogue.

A narrow window that should not be wasted

Taken together, Trump’s CPC redesignation and the launch of the U.S.–Nigeria Working Group offer a narrow but real window for change. The Nigerian government cannot easily ignore a formal designation that puts it in the same category as some of the world’s worst human rights offenders, especially when Congress is considering targeted sanctions on officials implicated in religious violence. The Working Group gives Abuja a way to demonstrate responsiveness and to channel U.S. pressure into joint programs rather than purely punitive measures.

Yet this opportunity also carries risk. If Washington’s concern for Nigeria’s Christians is perceived as primarily a talking point for domestic politics or as a pretext for coercive power projection, it could harden resistance among Nigerian elites and fuel nationalist backlash. If Abuja uses the Working Group to absorb pressure while continuing business as usual, recycling familiar promises without changing behavior, another round of disillusionment will follow, deepening the cynicism that many Nigerians already feel toward both their own government and Western partners.

The responsibility now lies with three sets of actors:

- The Trump administration, which must decide whether to invest political capital and resources in making the Working Group more than a photo opportunity. That means insisting on benchmarks, sustaining engagement beyond a single meeting, and resisting the temptation to declare premature victory.

- The Nigerian government, which must move beyond denial and accept that decades of “guaranteeing religious freedom” on paper have not prevented severe violations in practice. Real leadership would mean embracing the Working Group as a chance to fix systemic failures, not just to manage optics.

- Nigerian and international civil society, especially Christian communities and human rights organizations, which should use the CPC designation and the Working Group as leverage to demand concrete, measurable changes, not simply to celebrate a long‑awaited label.

Nigeria’s Christians and other vulnerable communities do not need more statements; they need to see soldiers arrive before the next attack, courts convict those who burn their churches, and political leaders treat their lives as equal to anyone else’s. The test of Trump’s new Nigeria gambit on religious freedom will be whether, months from now, it is possible to point to specific villages that are safer, perpetrators who have faced justice, and institutions that are stronger because of this Working Group.

If that does not happen, the CPC designation and the Abuja meeting will join a long line of well‑worded but empty promises. If it does, Nigeria might finally begin to move from crisis management toward a durable, non‑sectarian peace.